Oregon State University has a magnificent berry research center and I got to interview the lady in charge of berry production and research. We spoke about their advancements into blackberries that taste delicious without thorns. I happen to live on some property in the country that is sinking under the weight of wild blackberries so I’ll not be giving up my Himalayan blackberry crisp anytime soon, but for those home owners with room to grow some vines, thornless varieties seem like a great deal. This was published in August 2013.

Having a Berry Good Time

The Northwest’s berry research results in greater selection for the home gardener

By Vanessa Salvia

Many people know that berry crops grow well here in the Northwest thanks to our warm, dry summer days and cool nights. But this is not only a hospitable climate for berries, it’s also the center of berry cultivating research.

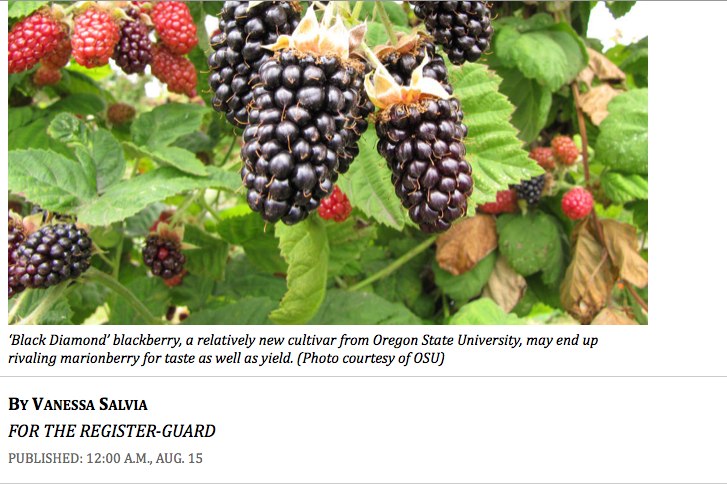

Dr. Bernadine Strik is Professor of Horticulture at Oregon State University, Extension Berry Crops Specialist, and lead researcher with Northwest Willamette Research and Extension Center at OSU. Strik researches production and physiology of berries and participates in the USDA-OSU cooperative breeding program to develop new varieties, one of which is a thornless blackberry known as ‘Black Diamond.’

“‘Black Diamond’ has become a very important variety in Oregon,” Strik says. The ‘Marion’ blackberry, commonly called the marionberry, was developed by OSU and released in 1956. The berry is a cross between the ‘Chehalem’ and ‘Olallie’ blackberries and was named after Marion County. “’Marion’ has a very distinctive, very aromatic flavor and it’s still the most important commercial variety grown in Oregon,” explains Strik, “and it is very important in the home garden but it is also very thorny.”

In 2005, OSU released ‘Black Diamond,’ which was the first variety released with an eye toward commercial processing. “No thorns, good flavor and it offers a really good choice for growers,” Strik says. “It has good firmness so it doesn’t turn to juice, and ease of harvesting. It’s been very hard to do so it’s been a long time coming to get quality thornless fruit.” Oregon has nearly 8,000 commercial acres of blackberries, the most in the United States. Approximately 75 percent of those acres are ‘Marion’ and ‘Black Diamond’. “We’ve produced a lot of good varieties in the last 10 years and what’s really exciting is that these are grown in large enough quantities to be available for the home grower,” Strik says.

Gray’s Garden Center’s Mike Bibbee says he’s seen an uptick in interest in thornless berries in recent years. Gray’s stocks a thornless dwarf raspberry called ‘Strawberry Shortake’ year-round, and can generally order ‘Black Diamond’ or other thornless blackberries on request. Bibbee says many of his customers don’t come in asking for thornless berries, but when they see them they’re intrigued. “If people walk in and see a thornless berry they think, ‘Ah, that’s an idea!’”

One of the things that people appreciate about blackberries is that they produce a lot of berries in a small space—in other words, they’re vigorous. But with that vigor comes difficulty in managing the crop size and spread. “‘Black Diamond’ has less vigor but higher yield than ‘Marion,’ and it’s thornless,” explains Strik. “Less vigor makes it easier to prune and train. From a home garden perspective it’s just easier to manage.”

Scott Bergler is a customer service representative for One Green World, a Portland-based nursery that specializes in berries and vines. “My personal favorite thornless blackberries based on flavor are ‘Triple Crown’ and ‘Black Satin,’” he says. “The benefit is that these do everything that blackberries do but they don’t have thorns so you can get to them more easily. You can let your grandkids get involved and run around without hurting themselves.”

In addition to varietal research, Strik focuses on organic blackberry production and impacts on productivity. She has received funding for a 4-year federal study following all the same regulations and restrictions that certified organic growers have on a 1-acre research site.

Strik says that the biggest challenge is weed management. Her team is studying how much weeds compete with blackberries, and how yield is affected by various methods of weed management. “We’ve compared weeds left alone, hand-hoed and landscape fabric,” she says. “We’ve had a tremendous yield increase with weed control. Last year we increased yield 67 percent if we hand-hoed compared to not weeding at all, and we double yield with weed mats compared to not weeding.” And, ‘Black Diamond’ yielded 15% more fruit than ‘Marion.’

Strik’s team plans to continue the study for another three years, but the results are so promising that ‘Black Diamond’ is surely here to stay. The predominant wild weed blackberry, the ‘Himalaya,’ is so common around here that it may seem nonsensical to plant a blackberry cultivar. But the ‘Himalaya’ berry is not as great as it seems.

“Commercial varieties don’t germinate regularly after they pass through a bird,” she explains, meaning that there’s less chance of a cultivar escaping and becoming invasive. “A ripe ‘Himalaya’ tastes very good but it’s not the same flavor profile as ‘Marion’— it’s higher sugar and lower acid. ‘Himalaya’ has very big seeds. I can make a marionberry or boysenberry jam and not remove any seeds and it’s wonderful, or a pie, but I can’t do that with a ‘Himalaya.’ It’s awful.”

Yet another reason is the narrow and rather late harvest window for ‘Himalaya.’ And finally, “There is no way you would want to manage a ‘Himalaya’ blackberry,” Strik says. “You talk about thorny? That thing is nasty.”

No comments yet.