This appeared in the July 2015 issue of In Good Tilth, the quarterly publication of Oregon Tilth, an organization that certifies farms as organic and works to protect and promote organic farming.

By Vanessa Salvia

The snowpack numbers are dismal. Six percent of normal in Pocatello, Idaho. One percent of normal in other parts of that state. Seven percent of normal in Oregon’s Willamette Basin and 11 percent of normal statewide, according to the Natural Resources Conservation Service—the lowest since 1992. Statewide, California’s snowpack is at 5 percent of normal as of April, making 2015 the driest winter in that state’s written record. The numbers don’t lie, but farmers knew something was going on by the amount of bare dirt where there should have been snow.

California, the state at the epicenter of the nation’s drought, produces more than 400 crops, and nearly half of the nation’s fruits, vegetables and nuts. California’s Central Valley is the world’s largest patch of Class 1 soils. It’s also the place where decades of irrigation have leached salts and minerals from the soil, creating a toxic ‘snow’ where plants won’t grow. This valley of food is nearly a valley of dust.

Last year, about 400,000 of these once-productive acres were fallowed. In 2015, the number could be twice that. But you can’t fallow an almond orchard. “Farmers down there are going to protect their most valuable crops,” says Karla Chambers, co-owner with her husband, Bill, of Stahlbush Island Farms in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. “You’ve got farmers down there looking at how to keep an avocado tree or a peach tree alive, not even thinking about harvesting, but just how do you keep that plant alive? And now those crops are going to go north or south, and the northwest will grow more crops as a result of there being those hundreds of thousands of acres not in production in California.”

Stahlbush Island Farms doesn’t disclose gallons of water used or pounds produced, but Chambers admits that while her farm hasn’t planted any different crops yet, it is growing more of the crops that aren’t being grown in California. “More of the nuts and fruits have come north and they’re going to be more expensive because of all those acres not in production,” she says. “California is just such an enormous player in our food market.”

Oregon Tilth supports research taking place at Oregon State University that helps organic and non-organic commercial growers producer higher yields of higher-quality fruit in more economical and sustainable ways.

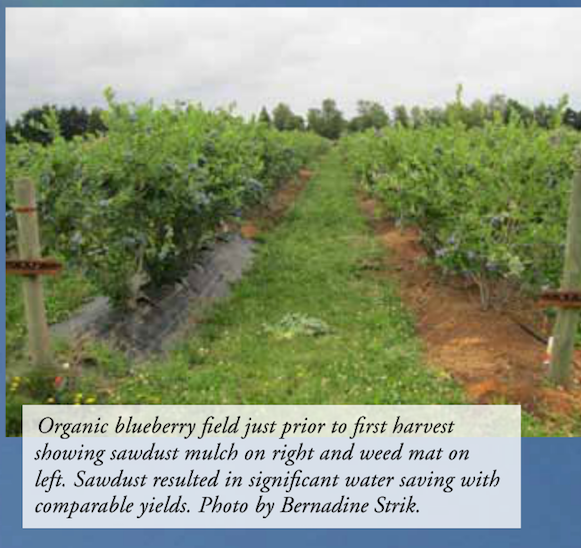

Bernadine Strik, a horticulture professor and lead berry crop researcher, has data from a blackberry research project that started in 2010 and just ended, and a blueberry research project that started in 2006 and is ongoing. In blueberries, the most economical way to manage weeds has been using a permeable plastic weed mat in the row. “What we have found is that using this changes the architecture of the blueberry plant, tending to produce a bigger canopy and a smaller root system,” Strik says. “We have monitored water usage over eight years, comparing that treatment to the more standard organic mulch like sawdust. What we found when comparing water use with this landscape fabric compared to sawdust is that water use is 30 to 50 percent greater with the weed mat. So there is a difference and growers understanding this difference is important.”

Strik’s research into blackberries resulted in another pleasant surprise for water reduction. Not only did they find that blackberries have a 60 percent reduction in yields if weeds are not controlled, they don’t need to be watered after the berries are harvested. In this as-yet unpublished research, after 2 years of collecting yield data and three years of not irrigating, Strik’s team found no difference in yield. “In the hottest part of the summer, farmers can feel comfortable skipping watering,” she says. “We have about 7,000 acres of blackberries in Oregon and if these farmers were not going to irrigate, that would save about 50,000 gallons of water per acre.”

Some farmers pay attention to the latest research and some don’t. “We see good attendance at our growers meetings but not all the growers are there,” she says. “You tend to see the same growers show up at these meetings and you wonder, where are the other ones? Some organic growers feel it’s not valuable to come to the meetings because they feel like it’s not focused on organic and I would encourage them to not think that because the practices are valuable to anyone.”

Bryce Crane, whose Bryce Crane Cattle Co. is Tilth-certified for barley, alfalfa and milk, raises about 200 head of cattle on a Montpelier, Idaho, ranch that was homesteaded in the early 1900s. Crane reported in early May that he was expecting his water usage to be cut by 50 percent by July. “We’re just going to pray for rain and hope it comes,” he says. “There’s nothing we can do.”

His irrigation comes strictly from snowpack-fed streams. If the drought gets worse, he’ll have to reduce the size of his herd or increase his acreage. Or pray harder. “It’s a challenge,” he says. “You’ve got to find a way to get through it. We’re worried. When the yields are down the income’s down and you just hope for the best.”

Wes Palmer and Natalie L’Etoile, owner of 15 acres along the Long Tom River in Noti, Oregon, are concerned and carefully considering their future options, which will likely include installing a rain collection system. L’Etoile Farm grows fruits and vegetables for a small CSA. They also have five Dexter cows that they harvest in spring, so the calves have the benefit of the lush, spring rain-watered grass. Their water right allows them to water up to 4.5 acres. But the Long Tom tends to run low, they say, and the old-timers in their area tell them this year could be bad.

If the water doesn’t come, they may have no choice but to fallow their land. “Each year farms face a lot of investments in seed and soil and soil amendments,” says Palmer. “So that would be the decision you would have to make . . . is it worth it to risk all this money and potentially not be able to irrigate it? But that’s what a lot of the farms are dealing with.”

Scott Clemons, Pubic Affairs Specialist for the Portland District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that oversees the Long Tom’s Junction City Water Control District, says that based on the water supply outlook and their own forecasts for reservoir elevation, they’re not anticipating difficulty in meeting water needs. “We are expecting Fern Ridge to come within a couple feet of full,” Clemons says. “Unlike many other reservoirs, there’s going to be a lot of sailors and birdwatchers who will be very happy.”

Karla Stahlbush says that despite the relative abundance of water in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, not a day goes by that she and her farmers don’t think about their water usage and worry about the future.

If anything good can be said to have come out of this cycle of historic drought that much of the West is experiencing, it’s that it’s brought public and political attention to the need to make changes in water usage.

Chambers also sees a large number of Northwest farms being “really proactive” about managing their water usage. “I include us among them,” she says, “in terms of being always, continually, looking for really efficient ways to use water. Farms are really looking at more sustainable ways to utilize water and all of us have a call to action to be more proactive in that area.”

The increasing scarcity of water in some areas of the country has every farmer worried. Sustainably minded farmers are either already using creative strategies to conserve and store water or they are taking action now to prepare them for future droughts. The state of alarm varies across the country, but throughout the arid west and south farms realize that diminishing groundwater and unfilled reservoirs are a critical concern.

Efficiently apply it

Jim Bahrenburg, the 72-year-old owner of North Fork Ranch in Kimberly, whose fields are watered by the North Fork of the John Day River, installed subsurface drip irrigation, or SDI, three years ago. He’s been farming without chemicals for 44 years and he doesn’t see that as a choice. “Mentally, I couldn’t do it any other way,” he says. “I can’t even conceive of using herbicides and pesticides. My motto is ‘Building the Soil We Depend On.’ It’s beyond the right thing to do, it’s, ‘we’re in trouble.’”

Bahrenburg’s system, which was designed by University of Nebraska irrigation engineer Suat Irmak, consists of irrigation lines buried 15 inches underground on lines between 500 and 600 feet long on two 20-acre fields. “Another neighbor I got on board with this is doing 20 acres too,” Bahrenburg says. “The drip emitters put out .26 gallons per hour and sprinklers above ground put out 3 gallons per minute. And then of course on a hot, windy day you’ve got evaporation.” A friend of his installed SDI over 1,000 acres at 18 inches below ground, which was determined to be too deep. “Someone told me to go to 12 inches but 15 inches is where you want to keep it,” Bahrenburg says.

Above ground drip applies about the same amount of water that the underground drip does, but, particularly when used for fertigation, it also ignites weeds. With the underground system, the water goes right to the root zone of the intended plants, keeping weeds at bay.

The current drought wasn’t the motivation for Bahrenburg to install this system. “I’ve known for years there was trouble coming water-wise,” he says. He doesn’t use moisture meters, although he could, instead relying on his feel for the plants. He could also control his irrigation system from a cell phone, but that doesn’t interest him either. One small computer would run 3,000 acres if he had that much.

He’s got the system programmed to irrigate every six days, for five monthly waterings. “I’ve calculated out that this will save about 2 million gallons a month over sprinkler irrigating,” he says. “But what I don’t know is, can I go 10 days in between my irrigating once I get the water bonded between the surface water and the sub-surface water? Can I get by going two weeks?” In this, his third year of using the system, Bahrenburg hopes to answer those questions.

Creative rot

Scott Goode, a farmer with 14 acres in hay that is flood irrigated and 4 acres in vegetable crops near the Rogue River, practices microfiltration and hugelkultur to maximize his water use. “I use biofiltration and microfiltration to purify water so that it’s adequate for our farm use,” he says. “Our irrigation water comes from Rogue River Valley Irrigation District and we’re on the very end of the line, so we get all the water that has flowed across everybody else’s land and picked up their dirt and chemicals and all that.”

He’s in the process of rebuilding a pond for catchment and he captures all the water that flows off the roof of his house. He’s installing a system of collection swales on a series of springs that flow well into the summer on his property and is putting that water into the pond. “We collect all the water through the winter and then use that water until our irrigation water comes on,” he says. “And then at that point the pond is switched over to a filtration system the irrigation.”

The Rogue River Valley Irrigation District has in recent years readjudicated some of its water rights. “A significant part of the water that used to be part of the irrigation district is no longer available and those are late season waters generally,” Goode says. “So by being able to store the majority of our water early in the season and then using that later we’re able to mitigate the loss of this late season water.”

Since the collection system is not completely in place yet, he’s still gathering data on how much water he’ll save. He does have data on hugelkultur, which at its simplest is a system of building raised beds atop a mound of decaying wood material. Hugelkultur, from the German word ‘hugel’ meaning ‘mound’ or ‘hill,’ replicates the natural process of decomposition under the surface of a forest floor.

“You can essentially bury rotting logs,” says Goode. “It sets up the perfect conditions for fungal communities to break down the logs and you can cultivate active crops on top of these berms, so you’re actually utilizing the space and the moisture and the fungal community. You’re able to grow crops that really respond well to fungal dominated soils like berries.”

One area of current research on this topic is to actively grow crops at the same time material that would normally be burned in logging slash piles is being broken down. Goode says the fungal composting system is a remarkable sequesterer of carbon, and there’s potential for these systems to be used in carbon offset programs.

What’s remarkable about it in a water-saving sense is that water vapor is one of the three components given off in any decomposition process in addition to carbon dioxide and ammonia or some other nitrogenous compound. “It gives off a significant amount of moisture so as these systems are breaking down the moisture that’s coming out of the decomposition of cellulose is going directly to the roots of the plants planted in the zone above it,” he says.

Goode is researching specific fungal communities and their efficacies in this process. He currently has three hugelkultur beds, one of which was just installed last fall. Goode created a lasagna-style compost bed with the foundation of the ‘lasagna’ layers resting on the woody material. This provides ventilation and drainage below the compost. When this system is properly inoculated with the right biology it will break down its materials much more rapidly than otherwise. “And as they’re breaking it down they give off moisture that feeds the layered composting from below,” Goode says.

These mounds become plantable beds over just a few months, and their water needs are dramatically less than a typical bed. “Certainly 50 percent less,” Goode says. “The reason is these compounds are so hygroscopic that in the morning when you get a dew, normally that dew would set on the land and then it will evaporate, but this system will absorb it like a sponge and draw it into your beds. That’s moisture you’re pulling out of the atmosphere that you don’t have to apply through irrigation.”

Plow it

Keyline plowing is another smart strategy for dry-land farming. Maud Powell and her husband, Tom, have keyline plowed the 11 farmed acres in their Central Point-area farm, Wolf Gulch, for 17 years. They conserve water by growing some crops for seed, which don’t need late-season water, and irrigate from 90,000- and 50,000-gallon rainfall-filled ponds.

The keyline refers to a topographic feature linked to water flow. The keyline plowing approach means identifying the ridges and valleys naturally sought out by water flows and plowing on those contours to allow water more time to sink in. “The idea is you want to keep as much water as possible as high as possible on the landscape so it slowly percolates through,” says Powell. Water winds its way slowly downhill, and lateral trenches plowed along the land’s contour lines allow it to do that most effectively, particularly when the soil has been enriched with a high humus content.

Store it

Melanie McAfee, owner of the country’s first certified organic event facility on a 7-acre farmstead property in Austin, Texas, just installed a 40,000-gallon ferrocement water tank.

The 3,000 square-foot solar grid atop their barn is perfect for water collection, as is the 2,000 square foot roof of their ballroom. The farm formerly used city water, which was expensive and not good for the plants, and the drought convinced McAfee that she needed to take steps. “We’re in drought and running out of water,” she says. “We try to utilize every drop we can.”

McAfee has been slowly transitioning the farm from an ornamental into an edible landscape. They used to grow 5% of their food and are now trying to grow at least half of what they consume. They have no data on the tank yet but they’re tracking their bills and are anxious to see how it plays out. “We’re pretty much neophytes at this point,” she says. “But we have not watered with our irrigation system since February.”

Nice article! If you’re ever in the Eugene area, feel free to come and check out our farm!